“We don’t know what it was but we had it

We don’t where it went but we lost it

And it may never come back again but I sure wish it would

We don’t know what it was but it sure was good” – George Jones and Tammy Wynette – “It Sure Was Good”

A lot of people have a “swing for the fences” mentality when it comes to investing. The general idea is that even if a lot of the investments lose money, that if one of them hits then it will hit big. They expect that the one success will more than offset the other losses.

And there are of course examples where that is the case. But even setting aside the fact that the market is fairly efficient (and that high risk investments are often “cheap” for a reason), limiting losses is more important than some people realize.

There’s an interesting phenomenon in finance sometimes called “Siegel’s Paradox”.

Let’s say that you have $1,000 invested in a stock and it goes down 10%. What gain do you need to get back to $1,000? 10%, right?

Oddly enough – wrong.

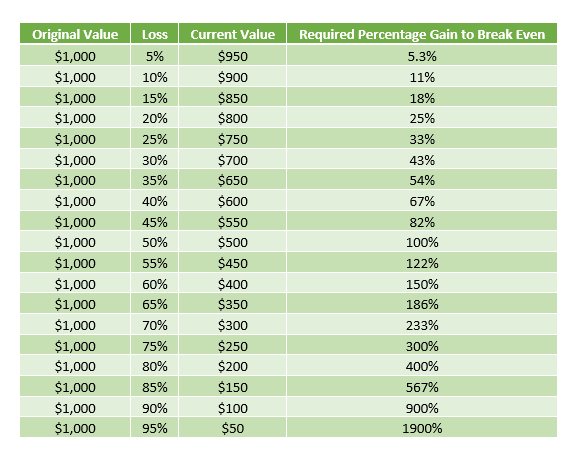

The stock value went down to $900. So to get back to $1,000 it will now take an 11% gain on its present diminished value. And it only gets worse the deeper the original loss was. A 20% loss would require a 25% gain, and 50% loss would require a 100% gain, and a 95% loss would require a 1,900% gain.

That makes sense if we step back and think about it. But we sometimes forget about the math. And for many, the first time they see it spelled out in cold, hard numbers is an eye-opener.

An investment’s price reflects its current value in the market. What we paid for it is irrelevant to the market. The market simply doesn’t care. So when investors say “I can’t sell it for $____. I paid ___!” it is somewhere between funny and sad. There are times that limiting losses via taking a smaller manageable loss is preferable to digging one’s heels in and letting the hit become so big that it takes a 1900% gain just to get even.

(It sort of reminds me of this: I always love it when you see listings on Craigslist in which people say they won’t take less than a certain amount because of what they paid for it. “We paid $1,200 for this TV so we will not accept less than $800 for it.” The TV is 10 years old and comparable ones are selling for $100. I really don’t care what you paid for it, Susan. It’s worth what it’s worth.)

So when an investment is devalued, it will take a greater gain/appreciation for us to break even. And when the average market rate of return is about 8% per year, it is going to take us a long, long time to make up for that 50% loss. This shows why finance professionals are always so focused on implementing appropriate risk management strategies in an effort to minimize your exposure to losses.

To be fair, ultra-safe investments have their own risks and downsides. But in all things – balance. Take appropriate, measured risk (or better yet, get a qualified financial advisor to do it for you), but don’t throw money around with reckless abandon just hoping you’ll hit the jackpot.

Any accounting, business, or tax advice contained in this communication, including attachments and enclosures, is not intended as a thorough, in-depth analysis of specific issues, nor a substitute for a formal opinion, nor is it sufficient to avoid tax-related penalties.