Originally Published May 2012

This is so broad a subject I hesitate to even try to fit it into one discussion. In my work I do a lot of research on natural gas. I don’t think any commodity is so widely talked about while being so woefully misunderstood. Lack of knowledge regarding industry operations combined with PR campaigns from gas industry and environmental groups have led to a mass of misinformation.

This has culminated in the following beliefs:

- New technologies have unlocked 100 years of domestic natural gas reserves

- Advanced techniques now allow more gas to be produced with fewer rigs and resources

- Because of the value of liquids being drilled for, “associated” (byproduct) natural gas can be profitable regardless of the price

- Because of the above two bullets, natural gas production will only increase

- Because of increased production, natural gas consumption can increase drastically while keeping the price within the $2-4/Mcf range

Regrettably, none of these claims are true. The amount of information that could be included here is immense. To try to avoid obfuscating the issue with excessive detail, I will try to keep it limited to main points.

Supply

Anyone who follows the energy markets has heard the claim: 100 years of clean energy. That sounds pretty great. Even if we doubled our natural gas consumption then we would have 50 years of supply – more than enough time to research alternative fuel sources. Unfortunately, the claim is outdated. The U.S. Geological Survey decreased their estimates to 20 years of marketable supply in August of last year. The issue?Marketable supply.

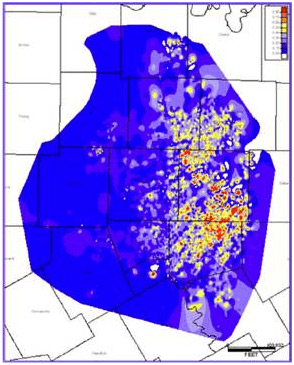

Geologist Art Berman has been spearheading this issue for some time. Shale reserves are vastly overstated for two reasons. First, the production from shale wells decreases 30-50% after the first year of production. In short, companies must constantly drill in order to maintain supply. Second, the reserves included in the original 100 year total are not economically viable to drill. That is, they are not concentrated enough to warrant the cost to extract the gas. Art’s graph of Barnett drilling highlights how concentrated the marketable reserves really are:

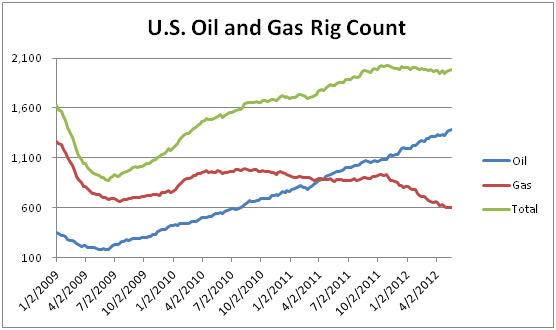

Priced into the market is the assumption that gas reserves are higher than they actually are and companies are making long-term decisions based on those beliefs. Yet at the same time, gas rig counts are constantly decreasing. The following shows rig data from Baker Hughes:

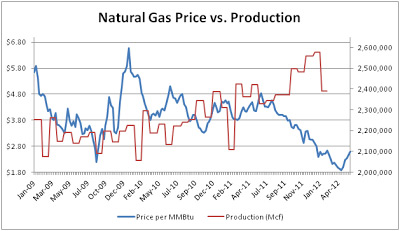

While associated gas from oil drilling has propped up natural gas production, it is not sufficient on its own. It is still a byproduct of the activity and is often flared. Low price has led to the decrease in gas rigs and the decrease in dedicated natural gas rigs appears to finally be decreasing withdrawals. We will discuss later why it has taken so long to do so.

Demand

Natural gas demand has been increasing drastically in the past few years, mostly in the domestic energy sector. The cheap price combined with an efficiency factor over coal generation has led to this being the most cost efficient fuel source. This is occurring at the same time when coal is getting hit with EPA regulations (CSAPR, MATS, CCS mandates on new plants, etc.) Installing the controls is extremely capital intensive ($500M+), which effectively regulates plants of <200MW out of existence. In addition, running the controls has a parasitic load estimated between 5-15% of the overall plant generation, which increases the cost.

Plants have to make long-term decisions at a time when environmental regulations are negatively impacting coal, natural gas prices are historically low, and the analysis by every energy firm is that those prices will stay that way. So given a weak electric market when these utilities are choosing which plants to run, which plants to close, and what new plants to build – natural gas has been their choice.

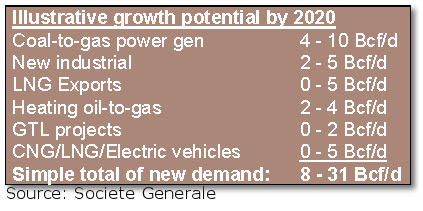

And while they have yet to make an impact on the market, there are several other opportunities for natural gas consumption. The price premium of international LNG over domestic natural gas prices makes LNG export very attractive if new terminals can get permits. Likewise, CNG and LNG vehicles are slowly gaining traction because of the low cost of natural gas relative to diesel. Clean Energy and other companies are working on natural gas trucking corridors to increase the possibility of conversion. The following from a natural gas convention in October of 2011 shows a summary of projected demand increases by 2020.

All of this paints a very rosy picture for the natural gas industry. But as any economist knows: the market always corrects. What is positive for demand is undoubtedly also positive for price.

Prices & Profitability

With supply likely stagnating because of the factors mentioned in the first section, increased demand will shift the equilibrium price. It has been estimated that a 2 Bcf/day increase in gas demand equates to a $2/Mcf price increase. Based on the gas industry’s projection above, that would theoretically increase natural gas to a minimum of $10.70/Mcf by 2020. This is a far cry from the $4.50 that is being projected by CERA and others.

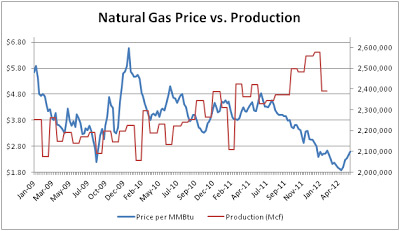

And in reality, supply has the very real possibility of not just stagnating but decreasing. Despite claims to the contrary by natural gas companies, natural gas needs to be somewhere between the $5.50-9.00/Mcf range for drilling to be profitable. Encana, Chesapeake, and others have been forced to announce cutbacks because of the low gas price and associated gas simply cannot fill the void in the long-term. The graph below shows how this is already starting to occur.

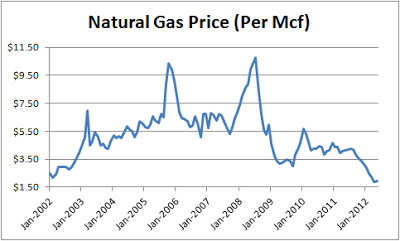

The graph below highlights how volatile gas has been within the last decade.

Bottom line: with demand increasing and supply at best remaining constant, price will increase. As it has throughout history, once enough conversion has taken place the price will spike drastically.

Other Miscellaneous Factors

The question that seems to have confused people and led them to agree with analysts who ostensibly have knowledge of the industry is this: “Why so long? Gas prices have been below marginal costs for some time. Why now? If prices haven’t already shifted, why would they do so now?” In addition to the reasons listed above, there are some mitigating factors that have gone into this.

The first is that new natural gas supply has outstripped pipeline capacity. As old pipeline routes have become obsolete due to new shale resources, the pipeline industry has not been building new pipelines as quickly as drilling companies have drilled new wells. This has created a massive supply glut with no outlet to utilities and other customers who would potentially buy the gas.

This supply glut combined with an unusually warm winter has created stored gas levels that have never been seen before. Storage capacity will likely fill up this summer – forcing drilled gas to either be capped or flared. This excess of stored gas creates excessive supply even as drilling and production decrease.

Then we must look at the drillers themselves. Savvy companies were able to take advantage of long-term price hedges. This enabled them to get a relatively premium price for their gas even as the market price was collapsing. These favorable hedges have now either expired or are soon expiring. Those same companies also had lease agreements that mandated that they drill with no consideration to price. Again, those old lease agreements are expiring and companies are not entering into new ones (read: decreased production).

Conclusion

The combined effect of this is fairly clear. Demand has and will continue to increase. If historic well depletion rates hold true and rig counts continue on their current path, supply will at best remain constant. And mitigating factors that have kept production and storage levels high are slowly going away. This will lead to further decreases in drilling until the inevitable happens when gas price goes back up and drilling becomes profitable again.

Might this take several years? Absolutely. But projections of a slow, incredibly stable increase in gas price for the 30 next years when it has been nothing but unstable in the past are patently absurd.